Juul, the vape device teens are getting hooked on, explained

Elijah Stewart first heard about the Juul three years ago, during his sophomore year of high school. Many of his friends had started sucking on the e-cigarette that resembles a USB flash drive. It was suddenly a lot more socially acceptable, even cool, “Juul” than to smoke cigarettes. Stewart was an occasional cigarette smoker when he began experimenting with Juul. Very quickly, he felt he was addicted. “After about a week, you feel like you need to puff on the Juul,” he says. “To some people it is like a baby pacifier, and they freak out when it's not near.”

Stewart, who is 19 and studies engineering at Providence College, now wants to throw away his Juul. Every four or five days, he burns through a pod — which comes in eight flavors, including Creme Brûlée and Cool Cucumber, and delivers as much nicotine as up to two packs of cigarettes. The habit sets him back about $16 to $32 every month. But quitting won't be easy, he says, because Juul is everywhere. “If you were to go to any party, any social event, there would no doubt be a Juul.” What Stewart is seeing on his campus in Rhode Island is part a dramatic shift happening across America: E-cigarettes have quietly eclipsed cigarette smoking among adolescents. The possibility of another generation getting hooked on nicotine is a nightmare scenario health regulators are scrambling to avoid.

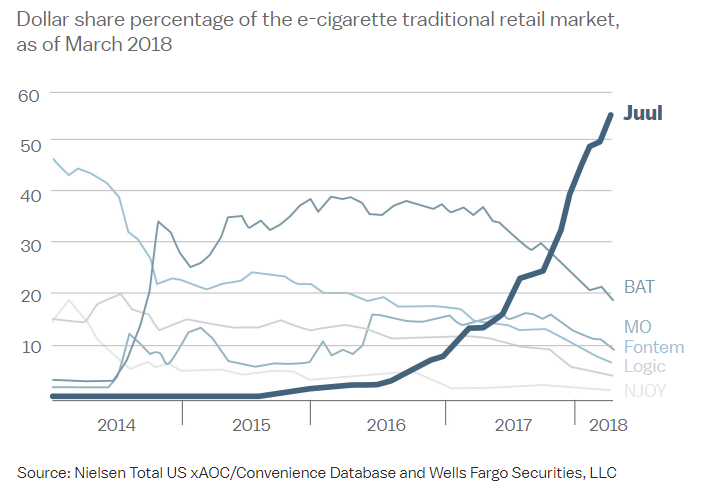

No device right now is as worrisome as the Juul — because of both its explosion in popularity and the unusually heavy dose of nicotine it delivers. In 2017, the e-cigarette market expanded by 40 percent, to $1.16 billion, with a lot of that growth driven by Juul. As of March, Juul made up more than half of all e-cigarette retail market sales in the US, according to Nielsen data. Considering it has only been on the market since 2015, and there are hundreds of other devices available to consumers, Juul's market share is staggering.

No device right now is as worrisome as the Juul — because of both its explosion in popularity and the unusually heavy dose of nicotine it delivers. In 2017, the e-cigarette market expanded by 40 percent, to $1.16 billion, with a lot of that growth driven by Juul. As of March, Juul made up more than half of all e-cigarette retail market sales in the US, according to Nielsen data. Considering it has only been on the market since 2015, and there are hundreds of other devices available to consumers, Juul's market share is staggering.

“I don't recall any fad, legal or illegal, catching on in this way,” says Meg Kenny, the assistant head of school at Burr and Burton Academy in Manchester, Vermont, who has worked in education for 20 years. Students at her school are Juuling in bathrooms, in class, and on the bus. Because it's against the school's rules, they hide the devices in ceiling tiles and in their bras and underwear. “Ninety-five percent of the disciplinary infractions we dealt with in the fall and continue to deal with into the spring are all connected to the Juul,” she added.

While administrators like Kenny are glad that cigarette smoke is disappearing from campuses, they're concerned that students don't understand the risks of using the Juul. What sets it apart from other e-cigarettes is that it hits the body with a tobacco cigarette-worthy dose of nicotine. We don't know if Juul is more addictive than regular cigarettes but it's certainly possible that teens getting into Juul now may be wading into a lifelong habit. While the long-term health impacts of e-cigarettes are still unknown, doctors and public health officials also worry about a range of immediate harmful side effects of nicotine on young people's developing brains and bodies. The “nicotine in these products can rewire an adolescent's brain, leading to years of addiction,” said Scott Gottlieb, the head of the Food and Drug Administration. There's also strong evidence that vaping may encourage young people to try cigarettes.

That's why Gottlieb announced on April 24 that the agency is cracking down on Juul and other e-cigarette companies like it, which appear to be selling and marketing their products to youth. The agency is going after retailers that illegally sell these products to minors, and they've asked Juul's makers, Juul Labs, to submit paperwork about their marketing practices and health impact. But the FDA, under Gottlieb, also delayed the compliance deadline for the regulation of e-cigarettes until 2022. This gave e-cigarette manufacturers who had products on the market before 2016, including Juul Labs, a free pass when it came to filing public health and marketing applications before selling in the US.

“In this world, a delay of [five] years is a lifetime,” said Matt Myers, president of the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. “And the data seems to indicate this product is being used by kids all across the country.” So what can and should be done about e-cigarettes like Juul, a growing market that Myers calls the “Wild West”? Let's break it down.

You can essentially Juul wherever without drawing much attention

E-cigarette sales have exploded over the past decade — and the devices have slowly been embraced by many in the public health community for their potential as a harm reduction tool to help smokers quit. Juul's stated mission is “improving the lives of the one billion adult smokers.” Created by two former smokers and Stanford design graduates (one of whom also worked as a design engineer at Apple), the duo wanted to make a device that looked sleek and attractive. So they designed an e-cigarette that could easily be mistaken for a USB flash drive — and can fit in the palm of the hand.

E-cigarette sales have exploded over the past decade — and the devices have slowly been embraced by many in the public health community for their potential as a harm reduction tool to help smokers quit. Juul's stated mission is “improving the lives of the one billion adult smokers.” Created by two former smokers and Stanford design graduates (one of whom also worked as a design engineer at Apple), the duo wanted to make a device that looked sleek and attractive. So they designed an e-cigarette that could easily be mistaken for a USB flash drive — and can fit in the palm of the hand.

The Juul has two components: the e-cigarette, which holds the battery and temperature regulation system; and the “pod,” which contains e-liquid — made up of nicotine, glycerol and propylene glycol, benzoic acid, and flavorants — and is inserted into the end of the e-cigarette device. Pods come in a variety of colors and flavors, from cucumber to creme brûlée, mango, and tobacco. Juul's “starter kit,” the e-cigarette, USB charger, and four flavor pods, sells for about $50. When you insert the pod into its cartridge and inhale through a mouthpiece on the end of the Juul, the device vaporizes the e-liquid. When the device runs out of power, you can insert it into your computer via a USB charger for a reboot. With such a sleek design and enticing flavor options, it's not difficult to see why these devices appeal to more than just older smokers.

“[Juul] is everything old vapes were not,” college student and Juul dabbler David told me. “It's very lightweight and portable, super easy to charge and refill, and it's low-maintenance,” unlike other e-cigarette devices that require users to replace coils or atomizers. But the biggest appeal for David is how discreet the device is. “You can essentially Juul wherever without drawing much attention.” For Stewart, the student at Providence College, it's also the flavors. “If they had bland flavors, then not as many people would [Juul].”

While Juul's official marketing campaign appears to be targeted to adult smokers, young Juul users have taken it upon themselves to spread the word. Campaigns have sprung up on social media, including #doit4Juul on YouTube, Twitter, and Instagram, where enthusiasts share photos and videos doing tricks with the product. Meg Kenny told me teachers often catch students Juuling in photos they've shared on social media.

Juul delivers a hit of nicotine like a cigarette. That's because of its “nicotine salts.”

Another feature that sets Juul apart from many of the other e-cigarettes on the market is the nicotine punch it packs. Each pod contains 59 milligrams of nicotine per milliliter of liquid. Juul claims one pod is equal to a pack of cigarettes in terms of nicotine, but tobacco experts told me the precise equivalency is difficult to determine because not all the nicotine released in cigarette smoke is inhaled, and some is trapped in the filter. Juul also contains three times the nicotine levels permitted in the European Union, which is why Juul can't be sold there.

Another feature that sets Juul apart from many of the other e-cigarettes on the market is the nicotine punch it packs. Each pod contains 59 milligrams of nicotine per milliliter of liquid. Juul claims one pod is equal to a pack of cigarettes in terms of nicotine, but tobacco experts told me the precise equivalency is difficult to determine because not all the nicotine released in cigarette smoke is inhaled, and some is trapped in the filter. Juul also contains three times the nicotine levels permitted in the European Union, which is why Juul can't be sold there.

Juul's creators ramped up the nicotine levels on purpose. They realized many of the e-cigarettes on the market don't hit smokers' systems in a way that's comparable to cigarettes. (Typical e-cigarettes have nicotine levels ranging from 6 to 30 milligrams per milliliter.) To address that gap, Juul vaporizes from a liquid that contains nicotine salts. In Juul, these nicotine salts are absorbed into the body at almost the same speed as nicotine in regular cigarettes, a speed that comes from the use of freebase nicotine.

But unlike the freebase nicotine in regular cigarettes, which can be very irritating, nicotine salt goes down smoothly and doesn't cause the unpleasant feeling in the chest and lungs that cigarette smoke does, said David Liddell Ashley, a former director of the office of science in the Center for Tobacco Products at the FDA. The vapor also doesn't have the nasty smell of cigarettes, and can emit a subtle whiff of fruit or other flavors when users vape.

“[That's] my biggest concern,” Ashley added. With traditional cigarettes, users typically cough uncontrollably on their first puffs. With Juul, vapers can get the same nicotine effect but without the pesky irritation. “It may be much easier for a user to start on these products,” Ashley said. Stewart says he also finds Juul more addicting. “It gives you a head rush that is stronger than a drag of a cigarette.”

Juul seems to have taken off among youth, many of whom don't know it contains nicotine

As regulators scramble over what to do about Juul, one thing has become clear: Many teens don't seem to understand the potential harms of these devices. A new study, published in BMJ's Tobacco Control journal, suggests many young people know about Juul, though they aren't aware of its potential harms. In the survey of youth ages 15 to 24, a quarter recognized Juul, and 10 percent reported both recognizing and trying the device. Alarmingly, most respondents were not aware that Juul pods always contain nicotine. “The actual true science behind [Juul] and the concentrate and how the nicotine is derived — that's not common knowledge to [students],” Kenny said. “And I think that's the work that we have to do and with our students and families. When we've intervened and had meetings with parents, they're even confused as to what's in the product. 'Is there really nicotine in it? My kid just told me it's flavored oil.'”

“[Juul's success] could be the first sign of a very important new category,” said University of Waterloo public health researcher David Hammond. “But here's the funny thing,” he added. The more appealing and cigarette-like an e-cigarette is, the better it competes with cigarettes, and the more it helps people quit. “On the flip side — the more likely it is to recruit new people into the market in terms of youth,” he said. “The nightmare scenario for public health is that this product brings kids into the market, addicts them to nicotine, and leads to smoking,” Hammond said. For now, it's not clear whether this is happening. But there seems to be good reason it could.